Race and Ethnicity in Antiquity Lecture Report

On the 24 November, Naoíse Sweeney talked on a very relevant topic in the world today, that of ‘Race and Ethnicity in the Ancient World’. In the modern day, race and ethnicity are fairly fixed, but in this talk we looked at several case studies that explored the very different attitude that was taken towards race and identity in the ancient world; something very important for us all to do, in order to remind us that our views of race and ethnicity are not shared universally.

The first case study that we explored was in Athens, in 422 BCE, and in particular, Euripedes’ Erectheus. This play centres around the mythical king Erectheus, at a time when the city was under attack by Thessalians. Upon going to the Delphic Oracle, the King is told that, in order to achieve victory, he had to sacrifice one of his daughters. While the King himself is in two minds about this, his wife is wholeheartedly for it, and gives a long and powerful speech arguing for the sacrifice. One point that was strongly stressed in this speech was the idea that the Athenians were autochthonous, an attribute which few Greek peoples could lay claim to, with most origins being from mythical migration. This shows, therefore, that the Athenians were very proud of their autochthony. We saw that this was further illustrated by the Erectheum sited on top of the Acropolis, which in turn shows that, at this point in history, the Athenians are, rather grandly, celebrating their status as indigenous. This was strange, as it, in a way, went against the idea of being Greek: the definition being an ethnic definition of Greekness, as we saw in the ‘Catalogue of Women’. In addition, this was not just a cultural idea in Athens; it was involved in politics and law as well. We saw this by the fact that, about 20 years prior, Pericles passed the law that, in order to be an Athenian citizen, both your parents had to be Athenian.

We also saw that, in Erectheus, Euripides also totally rewrites the genealogy of the Athenians. Originally, Ion, ancestor of the Athenians, is son of Creousa and Xouthos, the latter of which is the son of Hellen. However, Euripides makes it so that Ion is the son of Creousa and Apollo, which completely removes any element of the Athenians being Hellenic. At this time, it is important to note, the Athenians were at the height of their power, and are often the people we most associate with being Greek; and yet, they seemingly were trying to appear as being not Greek. This was, as shown by this first case study, the fundamental problem with the Greek idea of ethnicity.

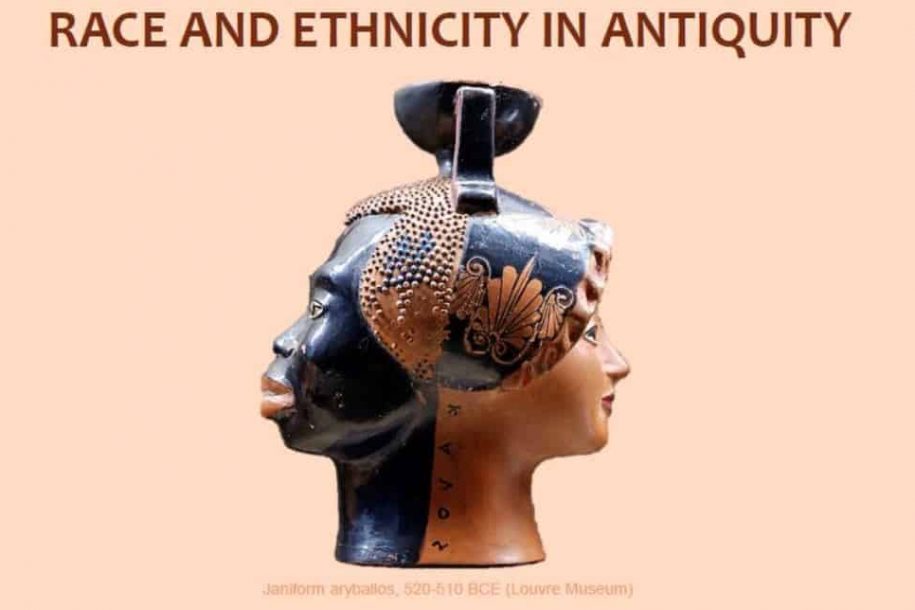

The second case study we looked at was exploring the intersection between ethnicity and race, in the form of the Gauls, or the Celts. At this time, an art style emerged known as Celtomachy, depicting ‘normal’ men fighting against the ‘barbaric’ Gauls. We saw that a key feature of this stereotyped depiction of the Gauls is a racial one, especially physically. Things that was especially stressed was the whiteness of their skin, the blondeness and thickness of their hair, and their height. While the Gauls were, as seen, very much defined by their physical features, the Germans were far more defined by their genealogical features. This key difference shows us that there are questions that are still unanswered about how race and ethnicity were related in antiquity.

Finally, we looked at the novel ‘Aethiopica’, by Heliodorus, a romantic fiction. It centers around lovers Theagenes and Chariclea, who are, at the end of the novel, prisoners of the Ethiopian King Hydaspes. They would have been executed had Chariclea revealed that she was a princess of Ethiopia. This saves them, and the couple are accepted. To prove her identity she produces several tokens, including her mother’s engagement ring and a note inscribed in her mother’s handwriting. However, Hydaspes is not totally convinced by this, as Chariclea is light-skinned, while her parents were dark-skinned (this is explained in that, at the moment of conception, the parents looked at the painting of a light-skinned woman, and so Chariclea got this woman’s characteristics. This shows that a shared descent and bloodline does not necessarily result in common bodily differences; ethnicity does not necessary match with race. In addition, genealogy matters less than physical sight.

To conclude, we learnt that race was not what we expect in antiquity; the intersection of race and ethnicity was not what we expect in antiquity; ethnicity itself was not what we expect in antiquity

Overall, this was a thoroughly interesting and topical talk.

Written by: Ruaidhrí (LGS Student)